Explore more in our Mag

There are times when your textbooks don’t help. The information can lack details or focus heavily on some other historical period, not what you really need. Instead of asking your groupmates for guidance with pleas like “Would you help me revise my essay?”, you can always visit our site to discover materials you won’t find on Wikipedia.

The story of Prussians – one of the Baltic tribes that strongly tried to resist the Crusades and Christianization in the 13th-century, but eventually they were forced to accept the new religion and their language became extinct in the later centuries.

Who were the Prussians?

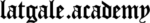

The Prussian name first appeared in written sources around the 9th-century, but more commonly this name was used since the 11th-century. However, this was not a united tribe with one ruler and law, but more of a group of ten clans – each of them had a name, based on their geographic location. Every clan had its own chieftain, but they all shared a similar language and pagan beliefs. When Teutonic Order began to invade their lands, Prussian clans occasionally united in raids and battles against their foreign enemy. They were praised as very brave and fearless warriors by medieval chroniclers. Prussians were reliable in battles; they fought to the death and attacked the enemies with great rage.

Medieval chronicles describe Prussians as very generous people that highly valued warm hospitality. For a host, it was not just about good manners. When it came to the wanderers and beggars, hospitality was a part of their beliefs that these strangers were sent to their homes by God. Baltic folk tales often include stories about God, who wanders around the villages dressed as a poor old man. Prussians believed that rejecting the guest might anger the divine being and lead to serious troubles in their lives. Hospitality was a kind of duty, sacrifice, and a sign of respect – all in one for the host.

Of course, they were not naive in this regard. Prussians were very protective of their borders and sacred places. If the guest entered their territory, he had to comply with the local laws and customs. If a guest showed respect, he had a warm welcome and the host was obliged to guarantee his security. Otherwise, if something bad would happen with a guest, his host would lose honor and respect of his clan. In case when a guest did not show enough respect, the meeting with Prussians could lead to a lethal outcome. The best-known example is the Adalbert of Prague, who was sent to Prussia by the King of Poland Boleslaw I and later executed by the locals after Adalbert tried to impose his religion on Prussians. He was warned by them to leave their lands and he paid the highest price for ignoring the warning.

Prussian beliefs & mythology

Religion had a special place in the Prussian life. The highest priest Kriwe-Kriwajto was one of the most important and influential persons in their society since the times of the legendary Prussian chiefs Widewut and Bruten. He had a great authority in the region and dozens of lower-rank priests worked under his command, such as wajdelotas. Some of them had the task to keep the holy fire burning under the sacred oak in Romowe – the central place of worship of Prussians, where they resided alongside Kriwajto. If fire extinguished, wajdelota, who was responsible for it paid with his own life. Romowe was the religious centre for all the Prussian tribes and it continued to exist even after the devastating attack of Poles in the early 11th century, who burned everything to the ground. However, Prussians fought back and soon restored their sacred place, and continued to preserve their beliefs with great enthusiasm.

Kriwajto performed all the most important rituals. He was the one Prussians truly trusted in cases of emergency when there was a war going on or some natural disaster causing devastation. The holy drink used in ceremonies was the mix of mare’s milk and honey. In opposition to the priests, there also were wizards and witches. Wizards were portrayed as controversial beings that could help and do harm to people depending on their character, while witches were generally known as evil beings – servants of the devil.

Since Prussian mythology was closely related to nature, there were dozens of various sacred places around the region – sacred forests, mountains, trees and stones that were surrounded by various legends. Some tales included the stories about humans, who were turned into the stones. Such human-like statues in Prussia were called babas. People occasionally tried to move them to another place or simply break them. However, in most cases, these statues were impossible to move and they remained in the same spot for many centuries. Locals, who knew the true meaning of these stones and trees – remained respectful long after accepting Christianity. They tried to avoid any disrespectful acts towards these sacred symbols of their ancestors.

While many of those stones were meant for sacrifices and rituals, honoring Gods – there were also some of those, that were linked with the stories about devil and his evil deeds in that particular area. Some stories told that the devil brought these stones on his back; others portrayed these stones as kind of tables, where devil played cards or dice, while also tempting people to give him their souls. When people tried to get rid of those devil’s stones from their area, it always ended without any success – the next night, the stone was back in the same place.

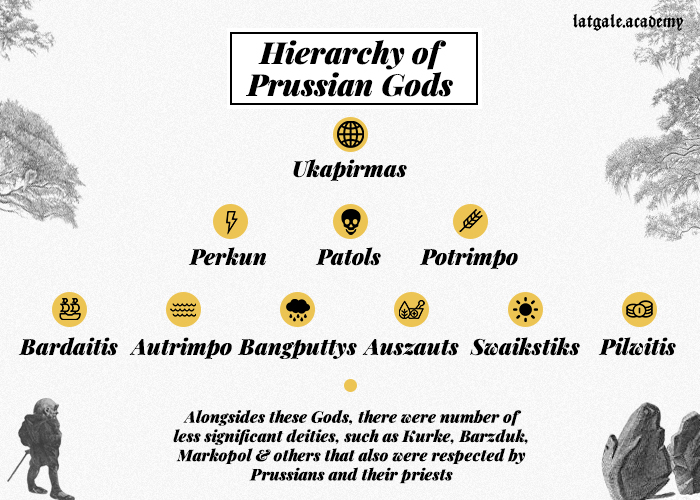

The hierarchy of the Prussian gods is particularly unclear due to limited sources from that time. However, it is clear that Prussians had a trinity of gods (Patols, Perkun & Potrimpo) that were worshiped at Romowe with great humility. Besides a geographical factor also played its role in the importance of the particular god. Those, who were farmers, did their sacrifices to Potrimpo (god of grain) and Pilwitis (god of wealth), while fishermen called for the help of the priest Udone, who did rituals, dedicated to the Autrimpo (the god of sea and lakes) and asking God for a successful catch in the sea.

There is a legend from 16th-century about the god of ships & sail – Bardaitis. At the time of the Polish-Teutonic War that lasted from 1519 to 1521, the fleet from Gdansk was approaching the coasts of Prussia and they called a wajdelota for help. The priest did his part and after his ritual, the Polish fleet was rumored to have serious hallucinations, caused by Bardaitis that forced them to retreat and stay away from the Prussian coast. Others knew Bardaitis as Gardoytis, who had the functions as Autrimpo and was worshipped by the Prussian fishermen.

Extinction of the Prussian language & culture

Why did Prussians give up their beliefs and their language disappeared? The short answer would be – because of the Teutonic Order and Germanization. However, there are a few nuances. Prussia was more of a religious confederation that consisted of several tribes. They had a Kriwe-Kriwajto as their common religious leader, but overall, each tribe still had its local chieftain and it lacked structure and unification in the battle against Teutonic Order. If they would have formed a united tribe, their resistance to the Christianization probably would have lasted longer, like it was for their neighbors Samogitians, who for 200 years fought against the German knights.

Crusades took a toll on Prussians, many were killed in battles and part migrated to the neighboring regions. Peasantry continued to maintain their old customs and beliefs long after they were baptized. Older generations carried the myths of the past and shared them with their descendants. Some Prussians continued to visit the sacred places of their ancestors to make sacrifices. As it often was seen in the former pagan lands – both religions could mix and have a dual nature. Prussians became Christians, but they remained largely superstitious. Nevertheless, Germanization did great damage to Prussian language and mythology and eventually put the end to its existence. Thousands of Germans settled in Prussian lands and they slowly became assimilated until locals completely forgot the language of their fathers that shared a similar fate as Sudovian, Galindian and Curonian languages that were similar to the Prussian tongue.

It is fair to say that the Prussian language saw its extinction around the beginning of the 18th century. People in the countryside still kept some of the old feasts and traditions alive, but it was more of a folk culture, not a religion like back in the day. There were no priests or any other religious structure attached to their pagan beliefs anymore. In some way, Prussians shared the same faith as the Native Americans, who also had their own language, religion, and traditions before the arrival of military more advanced Europeans. Different eras and parts of the World – the same fate.

Sources:

Endre Bojtar. A Cultural history of the Baltic people (1999)

Владимир Кулаков. История Пруссии до 1238 года (2003)

Algirdas Greimas. Of Gods and Men: Studies in Lithuanian Mythology (1985)